Happy Christmas, of course!

December 22, 2023 § Leave a comment

This year has been strange for me, as osteoarthritis in my left knee has kept me from most walking. I’ve now got a new half-knee, however, which seems to be working well. Things are looking up!

Sent from Outlook for Android

The strange hills

January 12, 2023 § Leave a comment

I was walking once in the hills. The track I was on was joined by another track coming in from the right. On this there was another walker. We greeted each other and walked along together. He claimed I was someone from his past, but I was sure I’d never met him before. As we walked along he described to me the track he’d been following before we met. Eventually we came to a fork in our track. There we parted. He went to the left and I went to the right. I never saw him again. The track I now was following was remarkably reminiscent of the one my former companion had described to me. I walked along it until eventually it was joined by another track coming in from the left. On this there was another walker. We greeted each other and walked along together. I was sure he was someone from my past, but he claimed he’d never met me before. As we walked along I described to him the track I’d been following before we met. Eventually our track forked, and at this fork we parted. I went to the left and he went to the right. I never saw him again.

After Hans Reichenbach, The Philosophy of Space and Time, 1958, Dover Publications Inc, New York, pp 141-142.

And yet another Christmas…

December 17, 2022 § Leave a comment

This past year has been strange, for various reasons, and one of the things that got lost in this strange year is my habit of blogging. Mind you, some people may have relished this, for some of the posts were getting more and more esoteric and apparently less and less walking related. But, anyway, it’s almost the end of the year, so a post of the old and familiar type will probably not go amiss. It’s my final Going It Alone article, which appeared in the April 2022 edition of Strider. Somehow it never got posted.

As always, to make the article legible simply click on the photo. If that doesn’t work, here’s the text:

“Designing a series of articles for a magazine – and I plan this article to be last in this series – is in one respect like designing a course of lectures. Into all but the final lecture you deliberately build a hook. You want your listeners always to leave asking “Yes, but what about?” The answer of course is “Come back next time!”

In the previous article in this series I identified the two kinds of problem that the go-it-aloner can be faced with on a long-distance walk: there are problems you can solve and there are problems you can’t solve. The hook built into that article is simply the question “What do you do, alone and miles from anywhere, if the problem facing you is one you need to solve but can’t solve?” Clearly things can go wrong when you’re going it alone – in some cases very seriously wrong.

It’s common wisdom that the best way to get out of a hole is to not get into it in the first place. The best way to solve a potentially serious problem would seem therefore to be to remove entirely the possibility of that problem arising. That, however, is a course of action no go-it-aloner will want to take. If you seek to eliminate the possibility of every potentially serious problem arising on a walk you’re planning, you’ll never leave home. By the same token, if you spend all of your walking time studiously avoiding everything that could possibly lead to a potentially serious problem, you’ll never get anywhere.

A more realistic course of action is to seek to minimise the disruption to your walk that potentially serious problems can cause. You do this when you’re planning the walk and also when you’re carrying it out. Whenever you identify a potentially serious problem you balance its severity (this is referred to as the danger) against the chance that it will actually arise (this is referred to as the risk). If the danger associated with the problem is low, irrespective of how low or how high the risk is, that problem is unlikely ever to disrupt the walk. You can effectively disregard it. If the danger is high but the risk is low, disruption certainly is possible, even serious disruption. The likelihood of disruption is nonetheless small, so you’ll probably decide to carry on. If the danger associated with a problem is high and the risk is also high, then you ought probably to ask yourself if you really do want to go ahead.

The words ‘danger’ and ‘risk’ are used in this context with very specific meanings. It’s therefore helpful to give a couple of examples of how this balancing of danger and risk can work in practice. The setting for the first example is Spitsbergen; the problem is that there are polar bears living there; the danger is that they will kill you. That counts – in my book at least – as serious disruption! The situation in Spitsbergen today is that the bear population is relatively large. Anyone moving outside a fenced area is strongly advised to carry a gun, and tented camps commonly post sentries. This is sensible, because the risk of being killed is otherwise unacceptably high. Now flash back more than fifty years to a group of student geologists working for several weeks in southern Spitsbergen. Four young men, two small open boats, two sledges, no radio, and a single gun – an 1896 Steyr bolt-action rifle. We weren’t always together when we were working, we camped always without sentries, and the rifle usually stayed in the mess tent. Our behaviour was not in any way irresponsible or unsafe. The danger involved in being killed by a bear was the same then as it is today, but the bear population then was relatively small. The risk of being killed was therefore acceptably low.

The second example is set closer to home, on the Ceredigion Coastal Path immediately north of Aberystwyth. You have two choices there for the section to Clarach: you can stay on the cliff-top path over Constitution Hill or you can take the geologically interesting route along the beach and spend a little time getting to know the Aberystwyth Grits. It’s your choice. The beach route has a problem, however, in that the coastline here is macrotidal, i.e., the tidal range is more than four metres. There are two cut-off points on the beach route, and you mustn’t get trapped between them on a rising tide. Getting trapped by the tide under an effectively unclimbable cliff is never a recipe for longevity, especially if the rocks and boulders at the base of the cliff are likely to be wet and slippery and the cliff itself is not everywhere stable. What is the risk of getting trapped? Look at the tide tables! If you take the beach route only on a falling tide or at low water you have next to no chance of getting trapped. If you cross one of the cut-off points on a rising tide and have insufficient time to clear the danger area, then you are certain to be trapped. You are in that case being extremely foolish. Don’t expect to be rescued. The emergency services are not there to compensate for your foolishness. This conscious balancing of danger and risk allows walks to be planned and carried out with the minimum of disruption. At the same time – because you get to set the levels of danger and risk that you are prepared to accept – it lets you make your walks your own. That is what going it alone is all about. You make the decisions and you take the responsibility for them. You get the enjoyment that results when things go right, and you accept the consequences when things go wrong. You know what you want to do, you know what you can do, and you know what you probably can’t do. So go ahead! Go it alone!”

Finally, to everyone who’s reading, a joyous Christmas and a wonderful New Year.

Continuity

January 20, 2022 § Leave a comment

Firstly, the documentation for the ants’ nest program is now on the ‘Software’ page at the left-hand side of the blog. This tells you how to download the program and how to run it. Have fun. I’ll be coming back to it in a couple of posts’ time.

Secondly, the flaws in those two magnificent films. First The Big Country. Play the clip (https://app.box.com/s/7k8tfgjmibi6au7khi152nar34hw6kia) and stop at 2:44. You’re looking down on the settlement, with the stagecoach coming into it fast from the top-right of the picture. There’s also a carriage drawn by a single horse coming into the settlement from the bottom-left. At 2:50, three horsemen ride in from the bottom-left of the picture and overtake that carriage. Now go on to 2:57. You’re now in the settlement looking at the stagecoach as it draws in. The three horsemen are now overtaking the stagecoach and coming straight towards you. To be able to do this they would have had to have zipped from one side of the settlement to the other at warp speed and changed direction 180 degrees. Oh!

Now to Lawrence of Arabia. Play the clip (https://app.box.com/s/oen791247pzp7qcv7n67w6yvomb5cmkp) and stop at 1:39. You’ve been watching Lawrence prepare his beloved Brough Superior SS100 before the fatal crash. He’s checked it, he’s polished it, he’s turned on the fuel, he’s put on his goggles, he’s grasped the handlebars, and he’s just kick-starting it. Now play the clip further. There’s first the continuation of the kick-start, then Lawrence mounts the bike, pushes it off its stand and rides away. The flaw is of course that up until the kick-start the surface on which the bike is standing is apparently a concrete slab – possibly a garage floor. Then, instantaneously, it becomes a gravel driveway. Oh!

Each of these flaws is a continuity flaw. It makes the film’s story not cohesive. This can be disconcerting for the audience. In some cases – All is Lost – it can be extremely disconcerting. You’ll find a brief introduction to film continuity in https://beverlyboy.com/filmmaking/what-is-continuity-in-film/

Continuity isn’t just something that film makers are concerned about. Scientists need to be concerned about it too – geologists perhaps more than most. Why? Come back next time!

Perhaps I’m not so bad after all!

January 5, 2022 § Leave a comment

That video clip you downloaded last time – you did download it, didn’t you? – has some great music in the background – Jerome Moross’ brilliant theme for William Wyler’s The Big Country. That’s a magnificent film, with its memorable opening sequence of the stagecoach crossing the prairie. Check it out at https://app.box.com/s/7k8tfgjmibi6au7khi152nar34hw6kia

Clearly this film’s got nothing at all to do with ants, so you’re naturally wondering why I’m referring to it here. The reason is simply that a couple of days ago I wanted to see that opening sequence again. As I was playing it I was thinking back to that algorithm of mine that I’d thought was flawless but turned out not to be. I looked at that piece of Wyler’s magic and thought, “This, at least, is flawless”.

And then of course I found a flaw – a not insignificant one. It’s blindingly obvious once you see it. How on earth did Wyler – truly one of the great directors, a man with a reputation as a perfectionist – how on earth did he let that get through? Look at the sequence for yourself and find the flaw! Hint: you’re not looking for something stupid like the white car parked on the side at the Battle of Stirling Bridge, in Braveheart.

OK, so Wyler wasn’t infallible. But David Lean surely must have been – the man who was perhaps the greatest director of all. Think Brief Encounter; think Bridge on the River Kwai; think Doctor Zhivago; think Lawrence of Arabia. I went straight to that brilliant opening sequence in Lawrence – the motorbike ride along the country lane and the ensuing crash – and again I thought, “This has to be flawless”. Check it out at https://app.box.com/s/oen791247pzp7qcv7n67w6yvomb5cmkp

Did I say there’s a flaw there too? And did I say that it’s also obvious? And am I wondering how Lean could have let that one through? Look at the sequence and find it for yourself!

Let’s make this a competition! Contact me with details of the flaws. There won’t be any prize for the winner, but all of the losers will be forced to sit through a screening of All is Lost.

The Ants’ Nest Problem (4)

December 27, 2021 § Leave a comment

You surely know the story! There you were, working contentedly away on some project. Then, for whatever reason, you broke off to do something else – and that something else went on and on, and on and on, and on and on. The project you’d been working on stayed stuck on the back burner for an almost interminable time. Eventually you got back to it, but when you did you found you’d lost your thread. That’s where I’ve been with the Ants’ Nest Problem. I’ll try and pick up that thread now, as best I can. Here goes…

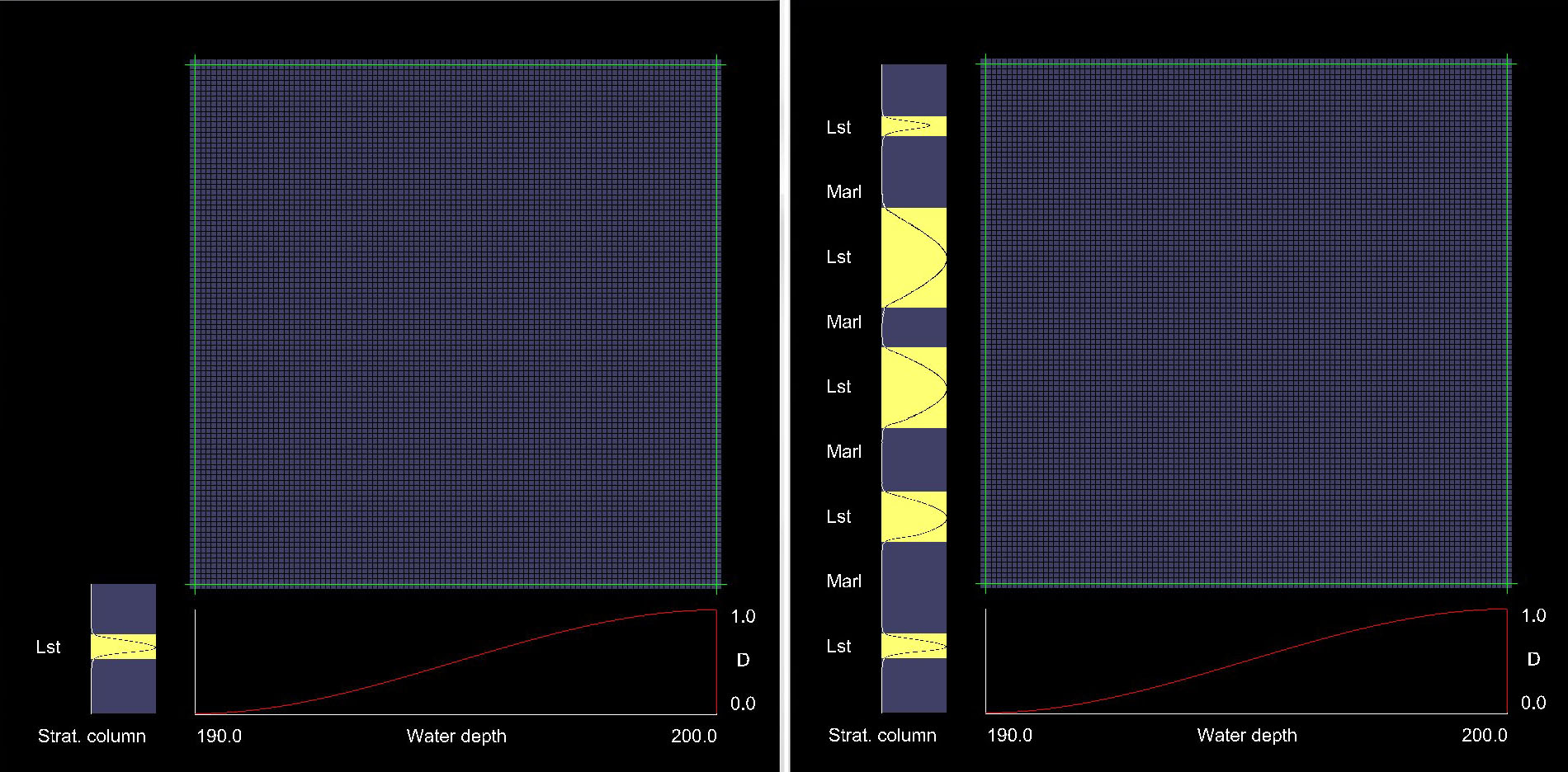

How can the Voronoi diagram be used to model how the ants in the nest move around without always colliding with each other? No problem! Remember, from last time, that each ant has a neighbourhood outside of which it never trespasses, and that this neighbourhood is defined by the Voronoi polygon constructed around the ant’s position. Each ant moves along whichever path it wants to take (determined by the parameters of the random walk), and it continues moving either (1) for a preset time step, or (2) until it reaches the edge of its neighbourhood, whichever comes first. The polygons in the Voronoi diagram are non-overlapping, therefore collision is impossible. The Voronoi diagram is recalculated at the end of the time step using the new ant positions, then the next time step begins. Like all really neat scientific models, this model is both reasonable and simple.

The model does nevertheless have a potentially serious difficulty, one that unfortunately is inherent in a lot of real-world geometric computing. Those of you who don’t do geometric computing can skip the next paragraph without missing anything critical.

The algorithm I use to construct the Voronoi diagram is one I developed about thirty years ago: https://app.box.com/s/cb9bvyu6kvf784xepggz8tfdvvck2fy7. It’s straightforward, it’s highly efficient, and it never fails. Or so I used to think. Sadly, however, I’ve found one instance in which it does fail. Here’s the context in which this failure occurs. The nest being modelled is square and has 270 ants. Potential edge effects are got rid of by wrapping the nest top-to-bottom and left-to-right, i.e., by surrounding it with eight identical copies. The Voronoi diagram has accordingly to be constructed for 2430 ant positions each time – a thoroughly manageable number that wouldn’t usually give any difficulty. The wrapping of the nest makes the x and y coordinates of the ant positions exactly cyclic, however, with the result that adjacent sides of the Delaunay triangulation can readily be effectively collinear. The precision with which the computer stores the position coordinate values will then be insufficient to allow the Voronoi diagram to be constructed correctly, at least in some situations. This is likely to be true irrespective of the construction algorithm used.

Am I going to spend the next few months of my life trying to get this algorithm of mine to trap this potential difficulty? I don’t think so!

To see that the model does in fact work, and to appreciate a little of what it can do, download this video clip: https://app.box.com/s/78i6fygir41icay5opubhymq21hsup5n

Try playing it. It shows three runs of the model, each run having approximately 1000 time steps. Here’s a snapshot to help you with what you’re seeing.

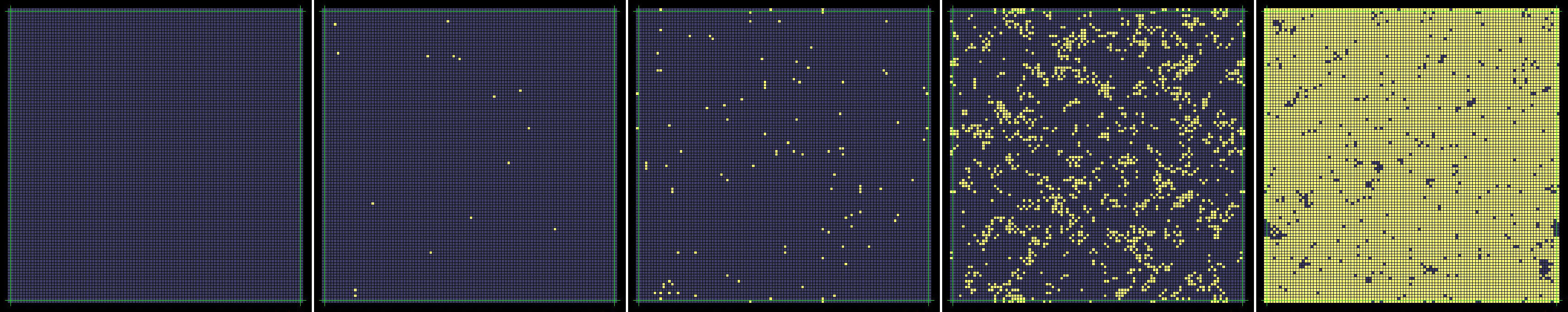

You’re looking directly down onto the nest, which is shown bounded by the (very faint) grey lines. You see immediately the top-to-bottom and left-to-right wrapping. So everything that goes out at the top comes back in at the bottom etc. The coloured discs represent the individual ants. A green disc is an ant that is fully separate from every other ant and can therefore move freely in any direction. Two or more red discs together are ants that are clustered: they can move individually, but they can’t move any closer to each other.

Each of the runs has the same number of ants (270), and most of the random walk parameters are the same (direction continuity = 2; maximum absolute direction increment = 10; standard deviation of step length increments = 0.01). The ants in the first run have no preferred movement directions, i.e., they are all moving truly at random. The ants in the second and third runs each have a preferred movement direction: half of them want to move from west to east, half want to move from south to north. The ants in the second run have no directional bias, either towards their preferred direction or away from it. The ants in the third run have a bias towards their preferred direction, i.e., they try always to move closer and closer to that direction.

Now play the clip again. The ants in the first run move very freely. There are a few clusters, always very small ones, and these clusters break up relatively quickly. The ants in the second run also move very freely, and you can clearly see the two preferred movement directions. There are now more clusters, but they’re still relatively small and relatively short-lived. The ants in the third run find movement much more difficult: they cluster together more and for longer periods.

So what’s the recipe for moving freely in an ants’ nest? Move at random. If you want to move on average in a particular direction, don’t always try to move in that direction; be prepared to move away from it at random, then come back to it later.

Two final points. Firstly, the ants’ nest program will be posted soon: look for it in the ‘Software’ page on the left-hand side of the blog. Secondly, there is a reason for the soundtrack on the video clip you downloaded – other than of course that I like Wyler’s film. Come back next time!

…and a present!

December 23, 2021 § Leave a comment

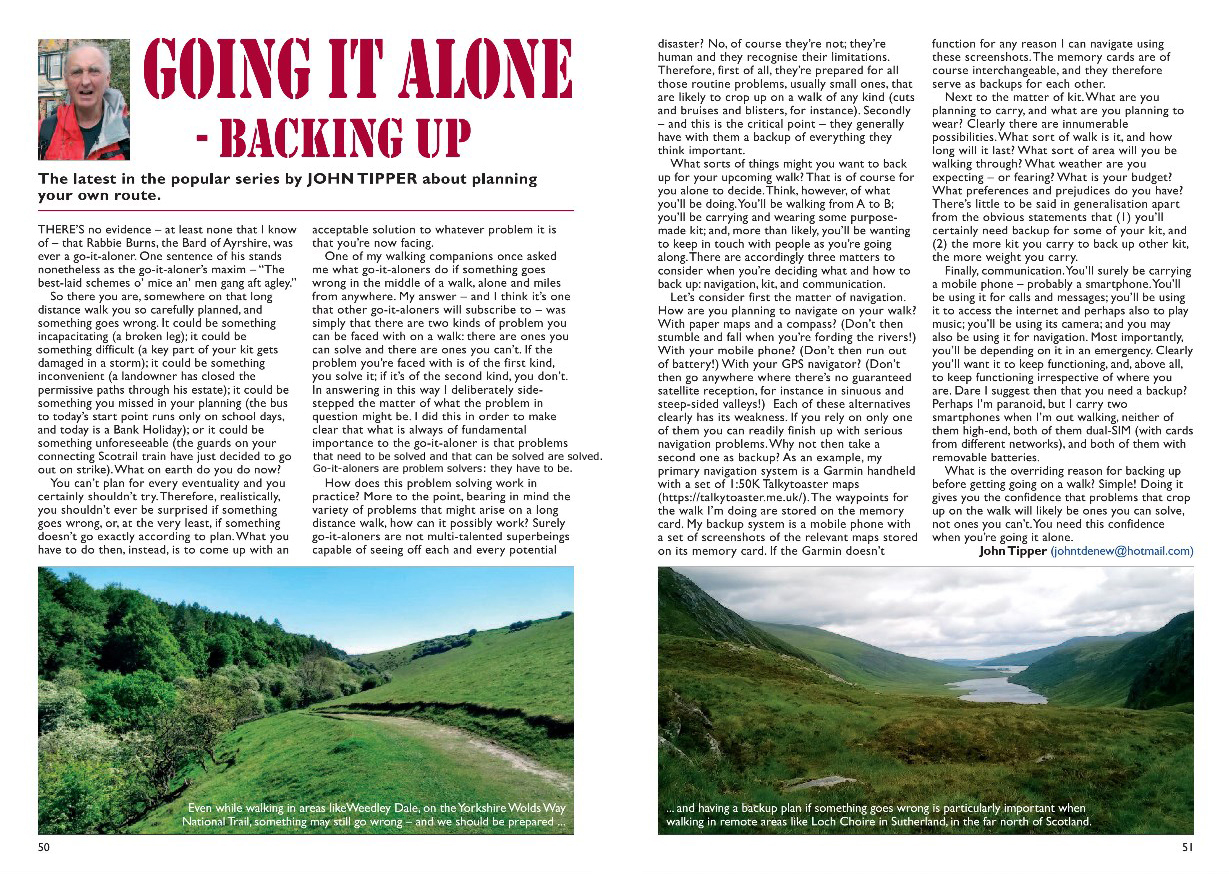

It’s a present to give you relief from the beer (Harveys, of course), the chocolates, the games you never really thought you’d get, the clothes you can’t imagine wearing, the books you swore you’ll never read, and so on. So what is it? The latest Strider, with yet another Going It Alone article! You always wanted that, didn’t you?

As always, to make the article legible simply click on the photo. If that doesn’t work, here’s the text:

“There’s no evidence – at least none that I know of – that Rabbie Burns, the Bard of Ayrshire, was ever a go-it-aloner. One sentence of his stands nonetheless as the go-it-aloner’s maxim – “The best-laid schemes o’ mice an’ men gang aft agley.”

So there you are, somewhere on that long distance walk you so carefully planned, and something goes wrong. It could be something incapacitating (a broken leg); it could be something difficult (a key part of your kit gets damaged in a storm); it could be something inconvenient (a landowner has closed the permissive paths through his estate); it could be something you missed in your planning (the bus to today’s start point runs only on school days, and today is a Bank Holiday); or it could be something unforeseeable (the guards on your connecting Scotrail train have just decided to go out on strike). What on earth do you do now?

You can’t plan for every eventuality and you certainly shouldn’t try. Therefore, realistically, you shouldn’t ever be surprised if something goes wrong, or, at the very least, if something doesn’t go exactly according to plan. What you have to do then, instead, is to come up with an acceptable solution to whatever problem it is that you’re now facing.

One of my walking companions once asked me what go-it-aloners do if something goes wrong in the middle of a walk, alone and miles from anywhere. My answer – and I think it’s one that other go-it-aloners will subscribe to – was simply that there are two kinds of problem you can be faced with on a walk: there are ones you can solve and there are ones you can’t. If the problem you’re faced with is of the first kind, you solve it; if it’s of the second kind, you don’t. In answering in this way I deliberately side-stepped the matter of what the problem in question might be. I did this in order to make clear that what is always of fundamental importance to the go-it-aloner is that problems that need to be solved and that can be solved are solved. Go-it-aloners are problem solvers: they have to be.

How does this problem solving work in practice? More to the point, bearing in mind the variety of problems that might arise on a long distance walk, how can it possibly work? Surely go-it-aloners are not multi-talented superbeings capable of seeing off each and every potential disaster! No, of course they’re not; they’re human and they recognise their limitations. Therefore, first of all, they’re prepared for all those routine problems, usually small ones, that are likely to crop up on a walk of any kind (cuts and bruises and blisters, for instance). Secondly – and this is the critical point – they generally have with them a backup of everything they think important.

What sorts of things might you want to back up for your upcoming walk? That is of course for you alone to decide. Think, however, of what you’ll be doing. You’ll be walking from A to B; you’ll be carrying and wearing some purpose-made kit; and, more than likely, you’ll be wanting to keep in touch with people as you’re going along. There are accordingly three matters to consider when you’re deciding what and how to back up: navigation, kit, and communication.

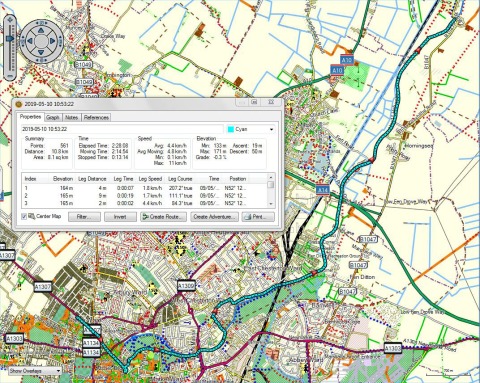

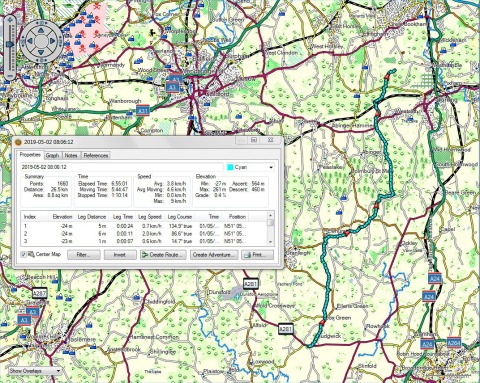

Let’s consider first the matter of navigation. How are you planning to navigate on your walk? With paper maps and a compass? (Don’t then stumble and fall when you’re fording the rivers!) With your mobile phone? (Don’t then run out of battery!) With your GPS navigator? (Don’t then go anywhere where there’s no guaranteed satellite reception, for instance in sinuous and steep-sided valleys!) Each of these alternatives clearly has its weakness. If you rely on only one of them you can readily finish up with serious navigation problems. Why not then take a second one as backup? As an example, my primary navigation system is a Garmin handheld with a set of 1:50K Talkytoaster maps (https://talkytoaster.me.uk/). The waypoints for the walk I’m doing are stored on the memory card. My backup system is a mobile phone with a set of screenshots of the relevant maps stored on its memory card. If the Garmin doesn’t function for any reason I can navigate using these screenshots. The memory cards are of course interchangeable, and they therefore serve as backups for each other.

Next to the matter of kit. What are you planning to carry, and what are you planning to wear? Clearly there are innumerable possibilities. What sort of walk is it, and how long will it last? What sort of area will you be walking through? What weather are you expecting – or fearing? What is your budget? What preferences and prejudices do you have? There’s little to be said in generalisation apart from the obvious statements that (1) you’ll certainly need backup for some of your kit, and (2) the more kit you carry to back up other kit, the more weight you carry.

Finally, communication.You’ll surely be carrying a mobile phone – probably a smartphone. You’ll be using it for calls and messages; you’ll be using it to access the internet and perhaps also to play music; you’ll be using its camera; and you may also be using it for navigation. Most importantly, you’ll be depending on it in an emergency. Clearly you’ll want it to keep functioning, and, above all, to keep functioning irrespective of where you are. Dare I suggest then that you need a backup? Perhaps I’m paranoid, but I carry two smartphones when I’m out walking, neither of them high-end, both of them dual-SIM (with cards from different networks), and both of them with removable batteries.

What is the overriding reason for backing up before getting going on a walk? Simple! Doing it gives you the confidence that problems that crop up on the walk will likely be ones you can solve, not ones you can’t. You need this confidence when you’re going it alone.”

Thanks, Santa.

Christmas Greetings!

December 22, 2021 § Leave a comment

It’s again that most important time of the year. So it’s all best wishes for Christmas and the New Year from theendtoendblog, to whoever might still chance to be reading.

And for those of you who still are there, here’s a rather special picture.

I took this photo in the late summer of 1968, lying face down on the beach WNW of Bautaen, in Hornsund, Spitsbergen. I was looking through the ice block directly north, for the sun was then at its lowest point in the northern sky. The hills on the left of the picture are on the other side of Brepollen, immediately to the west of Hornbreen.

A long wait

November 11, 2021 § Leave a comment

For all you dedicated readers of theendtoendblog, this has been an unconscionably long wait. Sorry!

The reason for the lack of recent posts – at least the primary one – is that Felicity and I have been involved here in a major piece of building work. I’ve been concentrating heavily on this, as opposed to ‘normal’ things like walking and blogging. The main part of the work is now finished (although work of this type is of course never truly finished), therefore there should be time in the next few weeks to get back to normality. I hope…

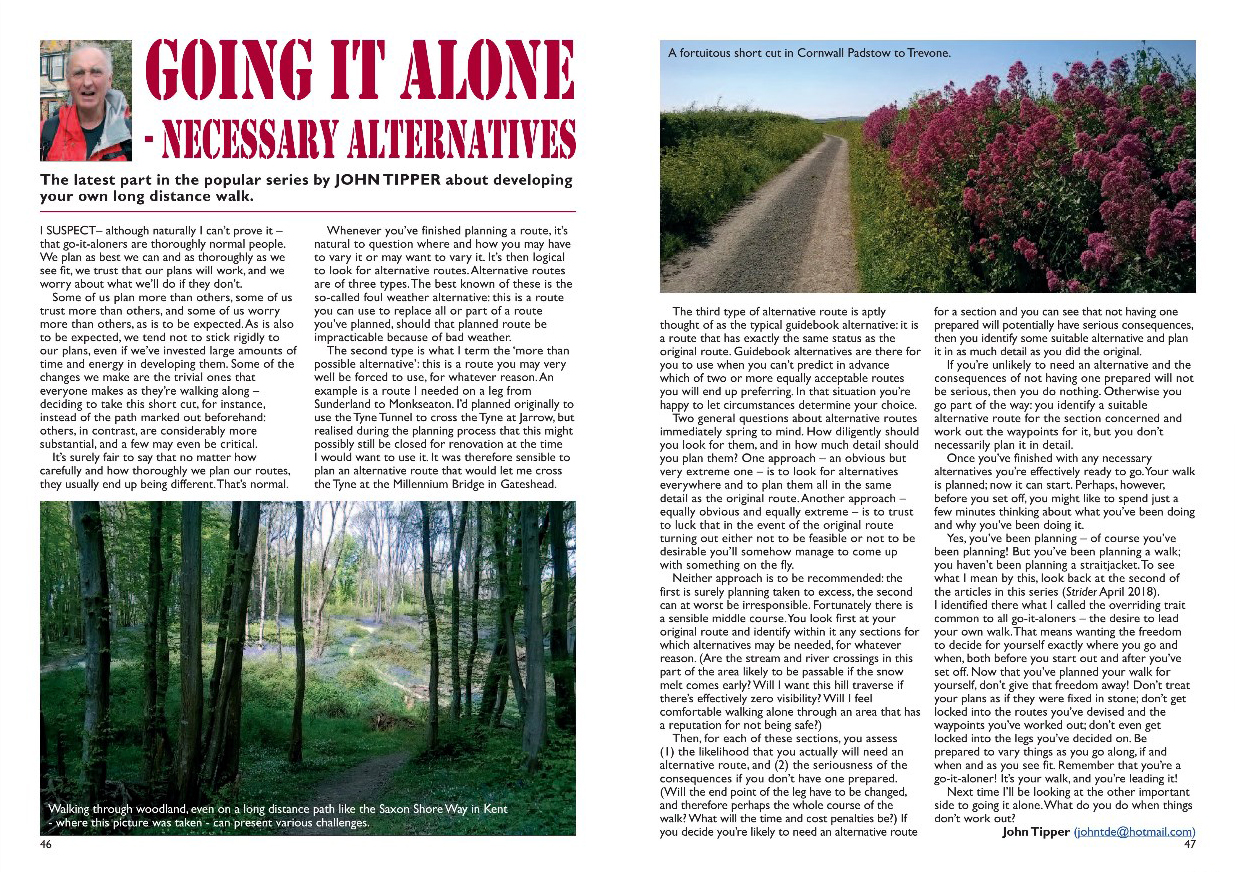

I’ll start by posting the latest Strider article. As always, to make the article legible simply click on the photo. If that doesn’t work, here’s the text:

“I suspect – although naturally I can’t prove it – that go-it-aloners are thoroughly normal people. We plan as best we can and as thoroughly as we see fit, we trust that our plans will work, and we worry about what we’ll do if they don’t. Some of us plan more than others, some of us trust more than others, and some of us worry more than others, as is to be expected. As is also to be expected, we tend not to stick rigidly to our plans, even if we’ve invested large amounts of time and energy in developing them. Some of the changes we make are the trivial ones that everyone makes as they’re walking along – deciding to take this short cut, for instance, instead of the path marked out beforehand; others, in contrast, are considerably more substantial; a few may even be critical. It’s surely fair to say that no matter how carefully and how thoroughly we plan our routes, they usually end up being different. That’s normal.

Whenever you’ve finished planning a route, it’s natural to question where and how you may have to vary it or may want to vary it. It’s then logical to look for alternative routes. Alternative routes are of three types. The best known of these is the so-called foul weather alternative: this is a route you can use to replace all or part of a route you’ve planned, should that planned route be impracticable because of bad weather. The second type is what I term the ‘more than possible alternative’: this is a route you may very well be forced to use, for whatever reason. An example is a route I needed on a leg from Sunderland to Monkseaton. I’d planned originally to use the Tyne Tunnel to cross the Tyne at Jarrow, but realised during the planning process that this might possibly still be closed for renovation at the time I would want to use it. It was therefore sensible to plan an alternative route that would let me cross the Tyne at the Millennium Bridge in Gateshead. The third type of alternative route is aptly thought of as the typical guidebook alternative: it is a route that has exactly the same status as the original route. Guidebook alternatives are there for you to use when you can’t predict in advance which of two or more equally acceptable routes you will end up preferring. In that situation you’re happy to let circumstances determine your choice.

Two general questions about alternative routes immediately spring to mind. How diligently should you look for them, and in how much detail should you plan them? One approach – an obvious but very extreme one – is to look for alternatives everywhere and to plan them all in the same detail as the original route; another approach – equally obvious and equally extreme – is to trust to luck that in the event of the original route turning out either not to be feasible or not to be desirable you’ll somehow manage to come up with something on the fly. Neither approach is to be recommended: the first is surely planning taken to excess, the second can at worst be irresponsible. Fortunately there is a sensible middle course. You look first at your original route and identify within it any sections for which alternatives may be needed, for whatever reason. (Are the stream and river crossings in this part of the area likely to be passable if the snow melt comes early? Will I want this hill traverse if there’s effectively zero visibility? Will I feel comfortable walking alone through an area that has a reputation for not being safe?) Then, for each of these sections, you assess (1) the likelihood that you actually will need an alternative route, and (2) the seriousness of the consequences if you don’t have one prepared. (Will the end point of the leg have to be changed, and therefore perhaps the whole course of the walk? What will the time and cost penalties be?) If you decide you’re likely to need an alternative route for a section and you can see that not having one prepared will potentially have serious consequences, then you identify some suitable alternative and plan it in as much detail as you did the original. If you’re unlikely to need an alternative and the consequences of not having one prepared will not be serious, then you do nothing. Otherwise you go part of the way: you identify a suitable alternative route for the section concerned and work out the waypoints for it, but you don’t necessarily plan it in detail.

Once you’ve finished with any necessary alternatives you’re effectively ready to go. Your walk is planned; now it can start. Perhaps, however, before you set off, you might like to spend just a few minutes thinking about what you’ve been doing and why you’ve been doing it. Yes, you’ve been planning – of course you’ve been planning! But you’ve been planning a walk; you haven’t been planning a straitjacket. To see what I mean by this, look back at the second of the articles in this series. I identified there what I called the overriding trait common to all go-it-aloners – the desire to lead your own walk. That means wanting the freedom to decide for yourself exactly where you go and when, both before you start out and after you’ve set off. Now that you’ve planned your walk for yourself, don’t give that freedom away! Don’t treat your plans as if they were fixed in stone; don’t get locked into the routes you’ve devised and the waypoints you’ve worked out; don’t even get locked into the legs you’ve decided on. Be prepared to vary things as you go along, if and when and as you see fit. Remember that you’re a go-it-aloner! It’s your walk, and you’re leading it!

Next time I’ll be looking at the other important side to going it alone. What do you do when things don’t work out?”

The Ants’ Nest Problem (3)

May 17, 2021 § Leave a comment

As I said earlier, this problem of the ants and their nest has two parts. For each of these there is a model, unsurprisingly. The first model outlines a way in which an ant can determine for itself the sort of path it will take; the second model shows how the ants can move around in the nest without continually colliding with each other. So far I’ve given details of the first of the models; it’s time now to deal with the second.

This second model is based on the simple idea that each ant deliberately restricts its movement always to its own particular neighbourhood; it never trespasses on adjacent neighbourhoods. “Neighbourhood”, you say. “Haven’t we heard that before?” The answer is of course that you have, in ‘The fashionable honeycomb’ (29 October 2020). Here’s the diagram I used then to illustrate three different types of neighbourhood.

Focus on the honeycomb mesh. One of its particularly attractive properties is that each of its cells is what is called a Voronoi polygon. (Many of you, I know, will want to read about this in the original French, so here’s the reference: Voronoi, Georges (1908) Nouvelles applications des paramètres continus à la théorie des formes quadratiques. Deuxième mémoire. Recherches sur les parallélloèdres primitifs. Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik 134: 198–287.) A Voronoi polygon is a polygon in which all of the points within it are closer to its centre – the solid black dot in the middle of the red hexagon – than they are to the centre of any other polygon. That’s clearly not true for the cells in the other two meshes.

OK, now to generalise things. The points at the centres of the Voronoi polygons that form the honeycomb mesh are regularly spaced: that’s why those polygons are identical in their size and shape. Voronoi polygons can nonetheless also be constructed for points that are not regularly spaced. They will of course then be different in size and shape. Here’s an example.

The Voronoi diagram (dashed lines) and Delaunay triangulation (solid lines) for a set of 15 data points (black discs)

Focus on the irregular pentagon in the centre of the diagram. It’s a Voronoi polygon. All the points within it are closer to the data point at its centre than they are to any of the other data points. That polygon is surrounded by five other Voronoi polygons. The data points at the centres of these are referred to as the Voronoi neighbours of the pentagon’s data point. Connecting together all of the Voronoi neighbours in the data set gives what is called the Delaunay triangulation. (Yes, here’s the original French for those of you who are desperate for it: Delaunay, Boris (1934) Sur la sphère vide. A la mémoire de Georges Voronoï. Bulletin de l’Académie des Sciences de l’URSS. Classe des sciences mathématiques et naturelles. 1934: 793–800.)

Back to the nest. Each ant is a data point; the Voronoi polygon for that point defines the ant’s neighbourhood; the Voronoi polygons surrounding that neighbourhood define the adjacent neighbourhoods. Simple really, but please pardon my French!

The Ants’ Nest Problem (2)

May 4, 2021 § Leave a comment

This post is short and sweet. OK, it’s short!

You were promised a program to experiment with – DRWALK. Here it is. You can get the documentation for it using the link in the ‘Software’ page on the left-hand side of the blog. This tells you how to download it and run it.

The pictures in the previous post gave some idea of the differences you can expect between random walks with correlated steps and random walks with uncorrelated steps. It seems to me pretty clear that the sorts of walks that ants do are best modelled using walks with correlated steps. Don’t believe me? Well now you can use DRWALK to see for yourself. Go on, try it!

Convinced? I hope so. Now try systematically varying the parameters for a walk that has correlated steps. This next picture shows the results of one such experiment.

A random walk with correlated steps, in ten consecutive parts (a – j). Each part has 1000 steps, starting at the point marked with a violet disc.

Each of the ten parts of this walk has a different combination of parameter values. These are summarised in the screenshots in the following way: ‘Continuity’ / ‘Maximum increment’ / ‘Bias’ / ‘Step length standard deviation’. Here’s the story: (a) low continuity and low maximum increment, therefore the step directions are concentrated around the starting direction; (b) maximum increment is increased, therefore the step directions are more spread out; (c) continuity is increased, therefore the step directions are less spread out; (d) maximum increment is decreased, therefore the step directions are concentrated around the direction being travelled at the start of that part of the walk; (e) bias away from preferred direction, therefore the walk turns slowly towards the E-W direction; (f) bias towards preferred direction, therefore the walk turns slowly towards the W-E direction; (g) maximum increment increased, therefore the walk turns faster towards the W-E direction; (h) continuity decreased, therefore the step directions, though they are concentrated around the W-E- direction, are more spread out; (i, j) step length standard deviation increased, therefore more possible variation in the distance covered.

Did I say short?

The Ants’ Nest Problem (1)

April 26, 2021 § Leave a comment

Some readers of theendtoendblog were surely convinced it would never happen: “He’s been promising us results from this ants’ nest work for an awfully long time and nothing ever comes. Typical!”

Well, sorry to disillusion you, but it’s showtime!

Two posts ago I introduced you to what for me is an intriguing little problem (‘Searching for a model’, 2 March 2021). The situation is as follows: (1) a large number of ants are moving simultaneously across the surface of a nest; (2) their overall movement pattern is presumably systematic (for instance to transport materials from one part of the nest to another), but there are no obvious regularities in the paths taken by the ants individually; (3) the ants manage to avoid colliding with each other. The problem – ‘The Ants’ Nest Problem’ – is to try to understand why and how the ants move as they do. (If you’re thinking you’ve already read a post about something that sounds suspiciously similar, yes you’re right. Check out ‘Models, and walking of course!’, 21 August 2020.)

The first step in addressing a problem like this is of course to come up with ideas about what is going on in the system concerned. Two ideas seem promising in this present case. The first of these is that each ant is continually deciding for itself which path it will take in the immediate future; it is doing this on the basis of information on (1) how it is moving at the time, (2) any preferred movement direction, and (3) its position relative to its neighbours. The second idea is that every one of the ants restricts its movement to its own particular neighbourhood; it never trespasses on adjacent neighbourhoods. (And yes, you are remembering correctly. You did read once before about the meaning and significance of trespass. Check out ‘Trespass!’, 13 January 2018.)

OK, those are the ideas; now to express them in a model. I’m going to deal with this in several posts: first I’ll cover how an ant decides on its path, then I’ll cover how it avoids trespassing.

It’s surely not unreasonable to suggest that any model for the movement of these ants should be a stochastic one. Firstly, the ants are behaving as separate entities; there is no Grand Old Duke of York directing them, nor is there an overall Master Plan that they have to follow. Secondly, the ants are living things; they are not inanimate physical objects. The movement of the ants will be modelled here as a random walk. (Yes, it is indeed déjà vu all over again! Check out ‘Walking at random’, 8 August 2020.)

There are in principle two types of random walk. One type – this is the one I described in that earlier post – has steps that are uncorrelated both in length and in direction. The other has steps that are correlated: the length of a step in a walk is obtained by adding a random increment to the length of the immediately preceding step, the same holds for the step direction. Within each of these types there is effectively unlimited variability. You can choose at will the frequency distributions you want, either for the step length and the step direction (for walks of the first type) or for the step length increment and the step direction increment (for walks of the second type).

An example or two wouldn’t be a bad idea, would it? And then perhaps a program to experiment with. OK, here goes. First the examples.

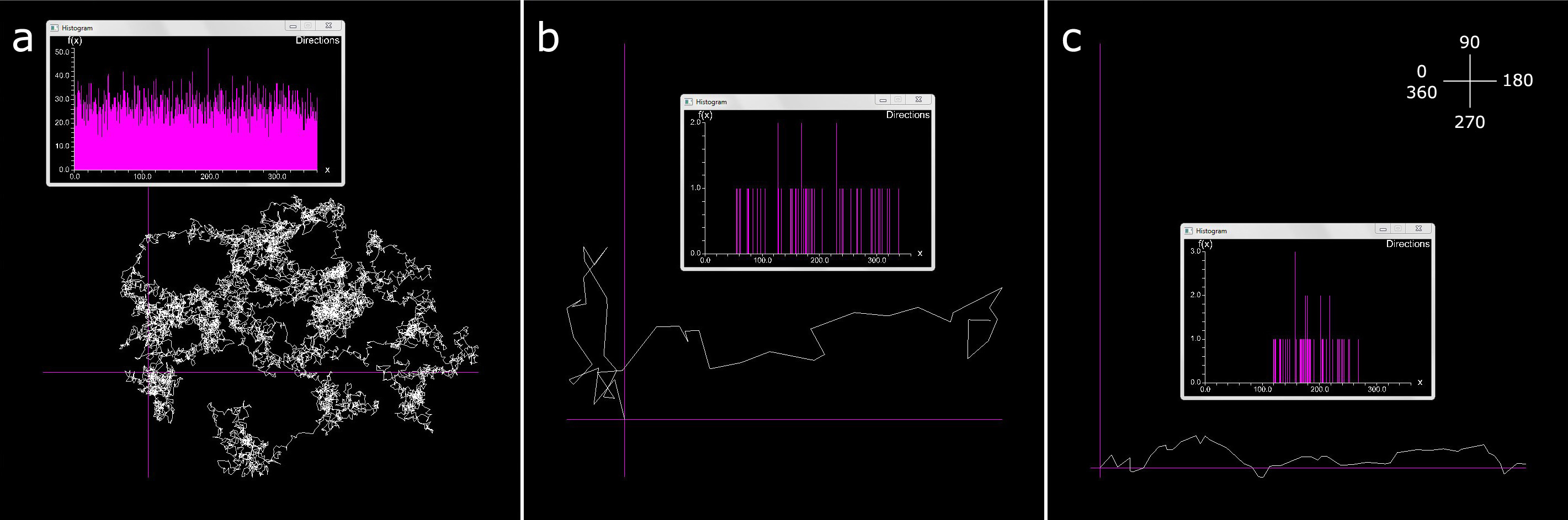

Random walks with uncorrelated steps: (a) no preferred direction, 10000 steps; (b) preferred direction, low directional continuity, 50 steps; (c) preferred direction, high continuity, 50 steps. Inset (top right) shows direction coordinate system.

Random walks with correlated steps and preferred direction, all for 10000 steps: (d) no bias; (e) no bias; (f) bias away from preferred direction; (g) bias towards preferred direction; (d, f, g) high directional continuity; (e) low continuity

What you’re looking at in each of these seven screenshots is a plot of a 2D random walk that started at the intersection of the purple lines. In each of the plots there is also a histogram of the step directions. The plots come from a program – DRWALK – that I’ll be introducing in the next post and that you can then experiment with. The walks in these plots are clearly different in their character; this is unsurprising because they were deliberately generated using very different frequency distributions. DRWALK controls the form of the distributions in five ways. Firstly, it controls the type of walk: uncorrelated or correlated. Secondly, it controls whether or not the walk is to have a preferred movement direction; this direction, if it is required, is fixed to be west-to-east, i.e., 180° in the coordinate system illustrated in the inset in (c). Thirdly, it controls the directional continuity, i.e., the degree to which the direction taken at any particular step follows either the preferred direction (for uncorrelated walks with a preferred direction) or the direction of the previous step (for correlated walks). Fourthly, it controls the degree to which the direction of a step is biased either towards or away from the preferred direction; this control applies only to correlated walks. Fifthly, it controls the mean and standard deviation of the step lengths or step length increments.

OK with all that? If so, great! If not, come back next time. You can then download DRWALK and play around with it to your heart’s content.

For anyone who’s been wondering…

April 13, 2021 § Leave a comment

Yes, theendtoendblog is still alive and well! First, there’s a new Strider article; then there’s progress in the matter of the ants. As always, to make the article legible simply click on the photo. If that doesn’t work, here’s the text:

“The immediately preceding articles in this series have dealt with three of the steps necessary in planning any substantial long distance walk: (1) breaking the walk into legs, (2) deciding, at least provisionally, on the routes for the legs, and (3) waypointing the routes. Wait! Don’t get your boots out yet! There’s still work to do! Those routes have first to be checked to see if they’re really what you want; then alternatives have to be prepared for sections for which alternatives are necessary. This work is going to take time – there’s no hiding that fact. It’s nonetheless going to be time well spent. Imagine that the walk you’re planning is one that’s going to take you out into the wild blue yonder, alone, for a month or more, and is not going to come cheap. It’s better to spend a little more time beforehand planning that walk than to spend a lot more time afterwards – either on the walk itself or after you’ve got back home – regretting the fact that you didn’t.

It’s at this point, before you start on this remaining work, that you’re going to have to make a critical decision. Which working methods are you now going to use? Are you going to work with guidebooks and maps on paper, or are you going to work on the computer? Both approaches are capable of giving satisfactory results and in the end it’s your decision. The essential difference between them is of course that a computer-based approach will be very much quicker than a paper-based one. I’m going to make three assumptions here: firstly, that you’ve decided to work on the computer; secondly, that your computer runs under Windows; thirdly, that your principal data formats will be .gpx and .kml.

Let’s see what’s involved in checking a route. For an example – this is an extremely straightforward one – look at the Google Earth image I’ve prepared. It shows part of a waypointed route along the Pembrokeshire Coastal Path, starting at the Copper Mine (the westernmost point of mainland Wales, southwest of St David’s) and finishing at Newgale. The checking process I use has four distinct steps; I’ll run through them in turn for this example.

The first step involves making a .gpx file of the waypoints. The software I use to do this is the GPS Route Planner available on WalkHighlands (https://www.walkhighlands.co.uk) and WalkLakes (https://www.walklakes.co.uk/). This program uses the 1:25K OS maps as its base and readily lets waypoints be inserted in the order of their decreasing importance, exactly as I described in my last article. Once you’ve inserted the waypoints you get estimates of the route length (17.3 km for the Pembrokeshire example) and the total height gain. The length estimate gives you a very rough lower bound for the time you’ll need to cover the route (3:28). You can ignore the height gain estimate because it assumes you’ll always be walking in a straight line from one waypoint to the next. At the end of the step you save your file.

The second step uses the route planning software again, but this time to fill out the route between the waypoints. This involves inserting an intermediate point at every change in route direction that you see on the map, no matter how small, and at every significant change of slope. There will be a lot of these points to insert – the Pembrokeshire route has 663. Don’t worry! With practice you’ll find they go in like a rocket; filling out the Pembrokeshire route took me less than half an hour. At the end of this step you’ll get a fresh estimate for the route length (20.9 km) and at last a usable estimate for the total height gain (797 m). From these two estimates you calculate the Naismith time in the conventional way (5:29). At the end of the step you again save your file. This time you make two versions of it – one in .gpx format and one in .kml format.

The third step is where the fun begins. Start Google Earth and load that .kml file. Now examine your route in detail on Google’s aerial mosaic. Look at it from above; look at it from the side; look at it obliquely; fly along it if you will, using the ‘Play Tour’ control. Some of the points you inserted in the previous step will certainly turn out to be wrongly positioned, either because of errors you made in inserting them or because of changes on the ground since the OS map was made. Reposition these points using the Google Earth path editor. Look for features visible on the Google Earth image that weren’t on the map and that can sensibly be incorporated into your route. Modify the route to incorporate them, again using the path editor. Check the types of ground surface your route will take you over. Will you be mainly on Council-maintained paths, for instance, with occasional climbs up grassy hillsides, or will you be trekking across His Lordship’s grouse moor with now and then some serious scrambling? There’s a mass of ground surface information visible in every Google Earth image, as in every aerial photograph, and you can supplement it if necessary using ground truth photographs, for instance from Geograph (http://www.geograph.org.uk/). This information is especially important because it greatly affects your estimate of the time you’ll need to cover the route. At the end of the step you save your modified route as a new .kml file.

The final step involves first converting this new .kml file to .gpx, for instance using KML2GPX (https://kml2gpx.com/?results). Then you load this file into the route planning program you were using earlier. This gives you length and height gain estimates for your modified route, together with a best estimate of the Naismith time.

Is this modified route satisfactory? Is it really what you want? Good! All that then remains to be done is to prepare any necessary alternatives. I’ll deal with that next time.”

And the ants? I’ve now found what seems to be a very reasonable model for the ants’ nest, which produces some fascinating results. The development and implentation of this model has required the solution of a few not insubstantial problems in geometric computing, so that’s why you haven’t heard much from me recently. Now, however, it’s showtime – well almost! Expect (D.V.) something in the next few days.

Searching for a model

March 2, 2021 § Leave a comment

A model? No, silly, not that kind of model! The model I’m searching for now is a scientific model – one that will help me understand the ants’ nest – another of those stochastic spatial processes I referred to last year (‘Another stochastic process – this time with thanks to David Attenborough’, 20 July 2020).

What so interested me in this process then – and this is the reason that I’m now searching for a model of it – is that it involves a large number of random walks taking place simultaneously over the same area. Each ant has its own walk, but those walks cannot of course be entirely independent of each other. Look at the film of the nest (https://app.box.com/s/1k8qsavsb1i4rdjc47a33843zgssx5p1). You’ll see that all the ants always in some way avoid collisions. The model I’m looking for must therefore allow for multiple random walks and at the same time incorporate what programmers refer to as collision detection and avoidance.

Dare I describe this rather ominously named field as being now a thoroughly standard one? Yes, because in the very great majority of situations the collisions to be detected and avoided are between inanimate physical objects. These obey the laws of physics, therefore they can be simulated readily using what are termed ‘physics engines’. A helpful overview of some of these is given in https://gdbooks.gitbooks.io/3dcollisions/content/Chapter7/engines.html, and a must-view example of one of them being used (https://pybullet.org/wordpress/) is in https://vimeo.com/373725595.

So why don’t I just put the ants into a physics engine and see what comes out? Simple! The ants are not inanimate physical objects, nor are their walks the deterministic paths that physics engines require them to be. There is animal behaviour involved, there is randomness, and – not least – there is for me the challenge of putting all this into a simple and usable computational framework. I’ve made a lot of progress over the past month but there’s still much to do. I’ll keep you informed.

Until then, you might like to check out Rex’s approach to the problem: https://www.dropbox.com/s/fnms8pkvhvrva09/Antz%20Pantz.mp4?dl=0

For your bookshelf

January 27, 2021 § Leave a comment

To those who might be asking why there’s not been even a hint of a post in the past few days, I would respond: “I’ve been sailing round the world with Slocum”.

One of the fixed points in the calendar, in the years we were in Canberra, was the Lifeline Bookfair. This raised – and it still raises – a major portion of the funding needed to keep Lifeline Canberra’s local crisis support service running: https://www.lifelinecanberra.org.au/lifeline-canberra/. The Bookfair worked as follows. You turned up on the day, at the Albert Hall on Commonwealth Avenue – not too late as otherwise all the good stuff would have gone – and you left a couple of hours later with boxes and bags full of books of all sorts, some of which you quickly got rid of, some of which you eventually got round to reading, and some of which you simply shelved for later.

At one of the fairs I picked up a copy of Sailing Alone Around The World, knowing only that it dealt with the first single-handed circumnavigation of the globe, by Captain Joshua Slocum. It fell into the ‘shelve for later’ category and so duly remained unread, sitting sandwiched on a shelf between Alan Villiers’ By Way Of Cape Horn and Thor Heyerdahl’s The Kon-Tiki Expedition. Two weeks ago, wanting something fresh to read, I opened it for the first time.

What a book! I’d expected a dry and tedious account of a long and at times surely monotonous voyage. What I found instead was an enthralling story of an amazing adventure. Leaving from Boston, in April 1895, Slocum crossed the Atlantic to Gibraltar, crossed it again to Brazil, crawled down to the tip of South America, fought his way twice (!) through the Strait of Magellan, crossed the Pacific to Australia then the Indian Ocean to South Africa, then finally hauled his way back up and across the Atlantic to Boston and home. He reached there in July 1898. What a voyage!

The story has a hero – Slocum of course. It also has a heroine – the Spray, the small nine-ton sloop that Slocum was given and that he then rebuilt. This hero and this heroine were ideally suited to each other: the hero with his experience and his courage, the heroine with her strength and her extraordinary sailing capabilities. Slocum was clearly never in any doubt of the debt he owed to the Spray. He gives credit always to her. He never seeks to put himself forward even when describing events that would strike terror into any normal person’s heart.

Slocum’s voyage took place in a world that for us today is foreign, a world that seems in so many respects to have been simple and direct. Slocum writes about this simple and direct world in a simple and direct way. That is his book’s charm. If you haven’t ever read it, now’s the time.

…sorted

January 16, 2021 § Leave a comment

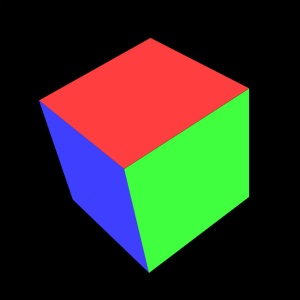

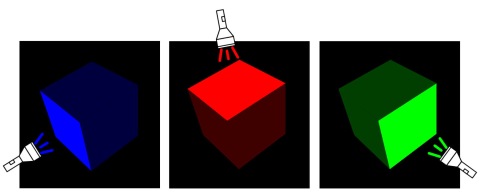

That’s an amazing image, isn’t it? Clearly a black hole isn’t something associated with an overheated ring donut; it’s a coloured cube. The three visible faces of this cube are of different colours – red, green and blue. That’s it! We’ve successfully imaged a black hole! What’s next on the agenda?

Not so fast! What was all that in the previous post about pictures not being pure unalloyed fact? About scientific data always being interpreted according to some model? Was there a model driving our interpretation of this image? If so, what was it?

Of course there was a model! And to work out what it was you’ve only got to think of how the image was collected (allegedly) and then interpreted. The collection was done at night using the most basic of smartphone cameras, one without a flash facility. The light captured by the camera had therefore to have come from whatever object it was that was being imaged. The interpretation of the image was done simply by looking at how the cube appeared. The top face appeared red, so naturally we thought it must be red; the right-hand face appeared green, so naturally we thought it must be green; the left-hand face appeared blue, so naturally we thought it must be blue. The model we were using – and we were using it instinctively – has as its principal hypothesis the idea that the cube’s faces are light emitters. They’re like coloured light bulbs: a red bulb emits red light, a green bulb emits green light, a blue bulb emits blue light.

There is an alternative model. This has as its principal hypothesis the idea that the cube’s faces are light reflectors, and in particular that they reflect light diffusely: see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lambertian_reflectance. This means that a face will automatically assume the colour of any light that is incident on it, irrespective of the direction from which it is viewed. This reflective cube would have appeared uniformly grey if we’d captured our image of it using a camera with a flash; the brighter the flash, the lighter the grey would have been. Our camera had no flash, however, so how was it that the cube was visible? Moreover, how could it appear coloured? The simplest possibility would be for it to have three associated external light sources – one red, one green and one blue – and for these sources to be fixed so that each is shining directly down onto a different face. The face onto which the red source is shining would be illuminated principally with red light; it would reflect this to the camera and therefore would appear red. The same would go for the other faces: the face onto which the green source is shining would appear green, the face onto which the blue source is shining would appear blue. Just as in the image.

The reflective cube without external light sources. L: no flash. M: weak white flash. R: bright white flash.

There are thus two equally legitimate models that can be used in interpreting the image, both of which work. They have radically different principal hypotheses. The second model has also an auxiliary hypothesis, namely that the external light sources exist. Which model should you choose? You takes your pick! Based on the image alone, there is no way to say. The first model is simpler – it has no auxiliary hypotheses – therefore KISS would recommend it: look once again at theendtoendblog’s ‘Ten Point Guide to Safe Modelling’. It is probably this model that most people looking at the image would think of first. Ultimately, however, it’s up to you to decide. You do this on the basis of your assessment of the models’ relative credibility. How you make this assessment is also up to you.

What a day! A black hole imaged and an irrelevancy sorted.

An irrelevancy…

January 14, 2021 § Leave a comment

One thing I like to do when composing the posts on this blog is to insert passages and references that seem irrelevant to the matter at hand. OK, so you’ve noticed! Why do I do this? Is it to frustrate you, my readers, and thereby to reduce the blog’s readership? Surely not! In fact it’s for a diametrically opposite reason, namely that I want to intrigue you, to get you to ask yourselves how on earth that passage or that reference possibly could be relevant, if not to the matter immediately at hand then perhaps to something important that’s coming up later.

One such passage was in the post ‘2019, with vivid memories from 1984’ (3 November 2020). Here it is:

April 10th saw scientists from the Event Horizon Telescope project announcing the first ever image of a black hole, one located in the centre of the Messier 87 galaxy. (Once again, this time for all of you who’ve simply forgotten: (1) the Event Horizon Telescope is a large telescope array consisting of a global network of radio telescopes; (2) Messier 87 – also known as Virgo A or NGC4486 – is a supergiant elliptical galaxy with about 1 trillion stars, in the constellation Virgo.)

What on earth has that passage got to do with the price of fish?

Check out this link: https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2019-04/nsf-acf040919.php. There you’ll find the scientists involved in the Event Horizon Telescope project trumpeting their success. There too you’ll find a video showing ‘the first direct visual evidence of a supermassive black hole and its shadow’. Here are two stills from that video.

The EHT black hole picture. L: original image. R: captioned image from video. Picture credit: NSF, Event Horizon Telescope collaboration et al.

Not being a hot-shot astrophysicist I can’t comment on what the first image shows; to me it looks suspiciously like an overheated ring donut. I can, however, comment on the second image, particularly on its caption. ‘Not simulation or conjecture…’ – you jest of course! The scientists and their paymasters are here selling you the idea that this picture is pure unalloyed fact. It isn’t! Like all scientific data – no matter how precise those data are and how carefully they are collected – the data used to construct this picture were subsequently interpreted. Critically, they were interpreted according to some model. That is how science is done. Remember what Medawar wrote: see ‘Truly magnificent stuff!’, 19 August 2020. If the model being used is altered, for instance by adding or removing auxiliary hypotheses or by varying the number and the values of its parameters, then the interpretation of the data necessarily changes. It is impossible to appreciate an interpretation of any scientific data without first knowing the model by which that interpretation was made. Sorry, astrophysicists, but that applies to your data too!

We really could do with an example here, couldn’t we? Fortunately there’s one readily at hand. It’s based on data that I believe pre-date those used to construct the EHT black hole picture. These earlier data were collected one starry night as theendtoendblog was meandering home after a pleasant evening with Arkwright at The Three Ferrets, with of course the obligatory John Smith’s (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UuVY6p6zdkI&feature=emb_logo). They were collected using the camera on a Nokia smartphone, this being a cheaper and suitably portable alternative to the otherwise unwieldy ‘planet-scale array of eight ground-based radio telescopes’. (If you believe any of this, you’ll believe anything!)

Here then is theendtoendblog’s image of a black hole. What is it exactly? It’s certainly not an overheated ring donut. Send your answers to theendtoendblog. Say firstly what it is that you think you’re seeing; then say what model it is that you’re using in making that interpretation. I’ll give you theendtoendblog’s answer next time. It may surprise you.

Now to Venice

January 10, 2021 § Leave a comment

Obviously we won’t be staying too long in Monte Carlo. This is because we need to get across to Venice for a bit of shopping. Initially we’ll take the coastal route, a part of the Camino de Santiago. Then we’ll cross the Lombardy Plain to Milan to check out the High Fashion scene – think back to 2013 (‘Models, and walking of course!’, 21 August 2020). Finally we’ll head down to Venice, again on part of the Camino.

I spent a good deal of time in the summer of last year discussing the matter of spatialness. I stressed then that you can’t study spatial patterns correctly – no matter what they are – if you ignore the fact that they are inherently spatial. I even devised a test to demonstrate this (‘Spatialness for Fashionistas 101’, 1 June 2020), which everybody duly failed (‘The test solutions, the take-home message, and some great music’, 3 June 2020). In the past few weeks I’ve been looking at something completely different – averaging. I’ve stressed that it’s necessary always to be wary of what averaging can do. These two themes – spatialness and averaging – come together in this present post.

OK, we’ve arrived in Venice. The photographers are waiting, understandably. They’re nonetheless a bit frustrated – you can see this on their faces – because this stunningly dressed lady keeps getting between us and their cameras. She is stunningly dressed, isn’t she? It’s a metallic silver pleated gown, from Alberta Ferretti in case you’re wondering. Look at that fabric! Look at the detail in it! Now step back and look at the grayscale version of the picture. There are four recognisably distinct parts there – the gown, the carpet, the photographers, and the background – and each of these parts has its own peculiar spatial pattern. What would happen to this picture, and to these patterns, if we were to apply some sort of spatial averaging filter to it? (If you’re not happy about what this means, look at the bottom of this post. There you’ll find a brief explanation of what’s going on.)

Each of the images in this diagram shows the result of applying a spatial averaging filter to the original grayscale picture. All but one of the images are steps in a sequence (1→2→3→4→5→6→7). The size of the neighbourhood over which the averaging is carried out for any of these seven sequence images is indicated by the white circle in the image’s top left-hand corner. These neighbourhoods increase in area by a factor of 4 at each step; the neighbourhood for the first image is approximately 4 pixels in area, the neighbourhood for the second is approximately 16 pixels in area, and so on. Image 8 is different from the others in that it is not formally part of the sequence. It should nonetheless be thought of as the sequence’s end-point. It shows the average greyness of the original grayscale picture.

Now be honest! The detail in the fabric of the gown is already lost in the very first image, i.e., with only the smallest amount of averaging; the second image is an acceptable representation of the original picture as a whole, but it isn’t acceptable for the gown and the photographers; the third and fourth images are sufficiently blurred that you wouldn’t want them in your photo album; the fifth image is recognisable as a version of the original picture only because you know what that original picture is; the sixth, seventh and eighth images could be anything. This is spatial averaging at work. It destroys spatial pattern, irrevocably. Averaging over even the smallest of neighbourhoods is sure to destroy fine-scale patterns. The larger the neighbourhood, the more complete the destruction will be.

The take-home message for this post is very similar in intent to that for the previous post. Firstly, again from theendtoendblog’s ‘Ten Point Guide to Safe Modelling’:

Beware of averaging.

Secondly – more specifically:

Spatial averaging destroys spatial pattern, irrevocably. Therefore never plug spatially averaged values into models of spatial processes, for instance to provide estimates of parameters.

Thirdly, enjoy Venice.

Each pixel in a grayscale image has an associated greyness value; this lies between 0 (= black) and 255 (= white). Spatial averaging involves replacing the greyness value of a pixel by a weighted average of the greyness values of all of the pixels in that pixel’s neighbourhood. This replacement is done simultaneously for each and every pixel in the image. The weights used for the averaging can be set in various ways. One possibility is to make them all equal: the new greyness value for the pixel on which the neighbourhood is centred is then the arithmetic average of the original greyness values. Another possibility is to make the weight used for a pixel depend in some way on the distance between that pixel and the neighbourhood’s centre pixel. This is commonly done using what is termed Gaussian blurring: https://www.adobe.com/ie/creativecloud/photography/discover/gaussian-blur.html#

Monte Carlo Revisited

January 6, 2021 § Leave a comment

Our previous visit to Monte Carlo (‘That white tuxedo … at last!’, 26 November 2020) furnished an example of how Monte Carlo simulation can be used to investigate the behaviour of models whose behaviour cannot be determined analytically. The model used in the example was the bushfire model (BUSHF1), and the object of the investigation was to see how variation in fire ignition capability affects mean instantaneous fire size and mean fire lifetime. (Yes, of course I’m going to be precise here: ‘mean’ means ‘arithmetic mean’.) The conclusion drawn from the simulation was that there seems to be some sort of tipping point in the model’s behaviour at an ignition capability of around 0.35. Fires with ignition capabilities less than 0.35 burn out naturally, some much quicker than others; fires with ignition capabilities greater than 0.35 rarely burn out naturally. The fires in the first group are not really dangerous; they may be inconvenient and therefore sensible to fight, but if all else fails they can be left to themselves. The fires in the second group are the dangerous ones; if they are not fought – by whatever means are possible – then they will consume much of what lies in their path.

Let’s assume now that we’ve been approached by Dodgy Brothers GmbH, a company that is seeking to become established in the field of bushfire prediction and control. They’ve come across the BUSHF1 program – perhaps by downloading it from theendtoendblog – and are interested in having us use it to estimate mean fire sizes for fires with known ignition capabilities. Yes, we can do that, and we accordingly design a suitably comprehensive programme of work. Naturally we quote our usual consultancy rates. We are rebuffed – unsurprisingly given Dodgy Brothers’ cheapskate reputation. They don’t want the work we’ve proposed; instead they want just two numbers – an estimate of the mean fire size for fires with ignition capabilities in the range 0.30 to 0.35, and an estimate of the mean fire size for fires with ignition capabilities in the range 0.35 to 0.40. They tell us we should get these estimates by running BUSHF1 for two ignition capabilities – 0.325 and 0.375. Their logic in saying this is that 0.325 – the arithmetic mean of 0.30 and 0.35 – is a best guess for the ignition capability of fires in the first group; similarly 0.375 – the arithmetic mean of 0.35 and 0.40 – is a best guess for the ignition capability of fires in the second group. “Always use the best guess for a model’s input,” they say, “then you automatically get the best guess for the model’s output. Best guess in, best guess out – that’s the rule!”

Oh dear!

This diagram summarises the results of four further Monte Carlo simulations run using BUSHF1. The histograms are for the fire size at a timestep. The left-hand histograms (green annotation) are for fires in the first group of ignition capabilities (0.30 to 0.35); the right-hand histograms (red annotation) are for fires in the second group (0.35 to 0.40). The upper histograms are for fires having the best guess ignition capabilities (0.325 and 0.375); the lower histograms are for fires having ignition capabilities spread evenly across the ranges 0.30 to 0.35 and 0.35 to 0.40. The calculated mean fire size for fires having the best guess ignition capability is not a good estimate of the true mean fire size. For fires in the first group it is an underestimate (16.56 against 19.40); for fires in the second group it is an overestimate (58.50 against 54.84).

This underestimation and overestimation is not specific to this example. It follows automatically from what mathematicians call Jensen’s Inequality: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jensen’s_inequality#:~:text=In%20mathematics%2C%20Jensen%27s%20inequality%2C%20named%20after%20the%20Danish,equal%20to%20the%20mean%20applied%20after%20convex%20. Savage termed this ‘The Flaw of Averages’ – a name that has stuck; see ‘Two Questions’, 3 December 2020.

To appreciate what’s involved in this, look at the inset plot at the top of the diagram. The relationship between mean fire size and ignition capability is convex-down to the left of the tipping point (green annotation) and concave-down to the right (red annotation). The mean value of a function that is convex-down is necessarily greater than the value of the function evaluated at the mean input (therefore 19.40 > 16.56); the mean value of a function that is concave-down is necessarily less than the value evaluated at the mean input (therefore 54.84 < 58.50). The only situation in which the mean value of a function can be guaranteed to be equal to the value of the function evaluated at the mean input is when the function is strictly linear over the range involved – a highly unlikely situation for any even halfway realistic model of a natural system.

The take-home message? Firstly, from theendtoendblog’s ‘Ten Point Guide to Safe Modelling’:

Beware of averaging.

Secondly, from an article on rock property estimation by two Stanford University petroleum geophysicists (Mukerji, T. and Mavko, G., 2008. The flaw of averages and the pitfalls of ignoring variability in attribute interpretations. The Leading Edge 27, 382-384 – once again I’m sorry that for copyright reasons I can’t provide you with direct access to the paper):

‘When there is variability and nonlinearity, calculations using single-point values are almost worthless. …Calculations based on a single “best guess” input may not give the “best guess” output. …One should not expect to get even correct average results using average values of inputs. …Simple simulations to account for the variability can be easily performed. Monte Carlo simulations…help to avoid the flaw of averages.’

Thirdly, enjoy Monte Carlo.

Fourthly, steer well clear of Dodgy Brothers.

Plans, and music

January 2, 2021 § Leave a comment

I can imagine what you’re thinking: “We’re hardly into the new year and already he’s posting. Hopefully he’ll get back to some serious walking rather than all that strange stuff he gave us last year.”

No such luck. There’s probably going to be a mixture of types of post – I write ‘probably’ because I can’t ever say what’s coming up next in this blog. (You didn’t really think this blog was planned, did you? More fool you!) The posts directly related to walks and walking will likely be limited in number. This is because (1) it’s winter time for the next two months, with snow and ice up on the Schwarzwald, (2) there are movement and accommodation restrictions in most of the areas I would like to walk in, and (3) the rebuilding work on our house is scheduled to start in mid-June, therefore I will have to be here at home for most of the summer and autumn. But keep the faith! Walking is not over – at least I hope not. (Oh, and there are of course more Strider articles sitting in the editor’s inbox.)

As to ‘that strange stuff’ – that’s certainly going to be continued. First there’ll be another visit to Monte Carlo; then some more about the meaning of average (pun intended); then a look at some of those other points in theendtoendblog’s ‘Ten Point Guide to Safe Modelling’; then… That should take me through ‘til March, which will mark the anniversary of a year’s rather special wandering. I’ve got a feeling this wandering will have been worth it. Once more, keep the faith!

Now to the promised music, to a link that Gisela sent me on Christmas Day. It’s a new recording of the Hallelujah Chorus, sung (remotely) by 350 voices and set in that most magnificent of Barcelona churches – Santa Maria del Mar. To see and hear this makes my heart soar.

Looking forward

December 24, 2020 § Leave a comment

Here, from theendtoendblog, are my very best wishes to you all, whoever you are and wherever you are, for Christmas and the New Year.

I’m looking forward to this coming year, to walking and to not walking, sometimes near and sometimes far, sometimes alone and sometimes in the company of my family and friends. Also, needless to say, to blogging!

Different words

December 19, 2020 § Leave a comment

theendtoendblog has striven always to be both correct and consistent in its use of language, albeit according to its own idiosyncratic lights. This latter freedom has let me insert dubious expressions into posts that otherwise would have been grammatically and syntactically exemplary. It has also let me be unreasonably critical of passages I’ve come across elsewhere, both in my native language and in German. Incorrect? Inconsistent? Moi? Surely not!

Many readers of this blog will take issue with me on this, especially in view of some of my more recent posts – I refer here to the ones that are liberally sprinkled with the words ‘average’ and ‘mean’. It’s not at all easy to see in these posts why I use one of the words in one place and not in another. Is this me being incorrect, or is this me being inconsistent, or is it simply me being lazy? Is there in fact any difference in meaning between the one word and the other? (N.B.: Here I’m considering only situations where ‘average’ and ‘mean’ refer to quantities such as size or amount, e.g., ‘the dress was of average length’ or ‘the mean weight was 20 kilogrammes’.)

There are three ways to clear up questions about the meanings of words. The first is to go to a reputable thesaurus, e.g., https://www.merriam-webster.com/thesaurus; the second is to carry out an internet search; the third is to do both. All three have their drawbacks. (1) The drawbacks involved in using a thesaurus are twofold: firstly, you spend large amounts of valuable time learning more about the possible meanings of the words you’re interested in than you ever wanted to know; secondly, you realise that anything is possible for the creative lexicographer. Synonyms, for instance, need not be synonymous; they can sometimes ‘differ in nuance’, where nuance means ‘subtle distinction or variation’ and subtle means either ‘delicate and elusive’ or ‘difficult to understand or perceive’. It’s all suspiciously reminiscent of ‘a petit soupçon of je ne sais quoi’ – with my apologies to the late JY. (2) The drawbacks involved in an internet search – for instance a search for ‘difference between average and mean’ – concern the credibility of the sites you reach and the answers you obtain. There are no official standards of credibility on the internet, obviously, so it’s up to you to decide what to believe. (3) The drawbacks involved in going to a thesaurus and at the same time carrying out an internet search concern the decision you have to make when the answers from your sources conflict. Do you opt for the answer from the thesaurus, purely because that thesaurus has a name and a reputation, or do you choose a more convincing answer from a completely unknown internet site? Once again, it’s up to you.

The relationship in meaning between the words ‘average’ and ‘mean’ is not at all difficult to understand. It’s therefore astonishing that lexicographers and internet site authors have managed so consistently to make such a pig’s ear of explaining it. The key to understanding the relationship is to recognise that both words are used routinely in two fundamentally distinct ways. Each is used as a general descriptor, and each is used with a precise mathematical definition. It is not possible to determine from the word itself the way in which it is being used; that can only be determined from the context in which it appears. The words, when each is used as a general descriptor, are synonyms pure and simple; they can therefore replace each other in the same sentence. The same holds also when each of the words is given the same mathematical definition. That’s it!

Some examples? Why not?

(1) The words ‘average’ and ‘mean’ are used in the following passage as general descriptors.

‘From Hargill Bridge I walked up and across the grouse moor south of Hagworm Hill. The moor here is a mosaic of patches of burnt and non-burnt ground. The burnt patches have a mean diameter of about 30 metres. My average speed was approximately four kilometres per hour.’

or equivalently

‘From Hargill Bridge I walked up and across the grouse moor south of Hagworm Hill. The moor here is a mosaic of patches of burnt and non-burnt ground. The burnt patches have an average diameter of about 30 metres. My mean speed was approximately four kilometres per hour.’

(2) The words ‘average’ and ‘mean’ are used in this next passage with a precise mathematical definition – in this case the arithmetic average and arithmetic mean.